You don’t need to be a tech expert to make good decisions about generative AI—but you do need to stay curious, ask the right questions, and know what your organisation can genuinely support. As the pressure to “do something with AI” grows, leaders everywhere are weighing up whether to build custom solutions, buy from suppliers, or pause entirely.

You don’t need to be a tech expert to lead well on generative AI for your organisation. Which is a relief to me personally, and probably to most of you. You do, though, need to pay attention and recognise the scale of the newest industrial revolution. You should understand why it matters so much, and you need to be curious about what’s happening elsewhere that you can learn from. Mainly, you need to ask the right questions and then make the best call you can, before you fall too far behind.

Right now, every leadership team in the world is trying to make decisions about whether to build something AI-flavoured in-house, bring in a supplier, or just hold off altogether. And – as with every other decision – you do it while weighing up how much information you need versus how long you can afford to pause while doing more research.

This isn’t just about procurement. As your list of ‘things we could do with AI that would have seemed impossible this time last year’ grows ever longer, it’s about knowing what your organisation can genuinely support, how to avoid overpromising, and how to work with your IT and digital teams without expecting them to solve everything by default.

Ever on a mission to make our advice immediately useful to you, we’ve worked up five practical questions to help you navigate these GenAI decisions and bring your tech teams with you.

1. What problem are we solving – and is generative AI the right fit?

It’s easy to get excited about AI’s potential to automate or streamline. But sometimes the problem being presented isn’t the real issue. For example, if staff are asking for help with case recording, is the problem really about the writing time/effort/quality, or is it that the system they have now is clunky, or that the guidance is unclear and they’re not confident in what they are expected to do?

Generative AI can be a powerful enabler, but it’s not a magic fix for deeper operational issues. The best solutions start with clarity on the underlying need so that form can follow function. If you want to turn some loose information into better drafted notes that are easier to verify and share, a large language model-powered AI solution can definitely help. If you have disconnected information in different systems, you have some data engineering to do. If people feel unsupported, there is still some good old-fashioned high-quality management of humans to do. If your old supplier sold you a clunky system that doesn’t meet your needs, look to your contract terms.

And, if you’re feeling behind, don’t panic. The good news is, no one’s got this completely figured out. But you can ask sharper questions and make decisions that are right for your organisation now, and that’s enough.

2. What data will it use — and is that data accurate, current, and appropriate?

AI outputs are only as good as the information they’re based on. If your policies are out of date, your training materials inconsistent, or your guidance hard to navigate, the AI will reflect those weaknesses (although it can help you identify and fix them too).

Ask:

• Where is the data coming from?

• Is it maintained regularly? Do we know who’s accountable for the supply and quality of it?

• Do we trust it enough to make decisions?

Clive Humby* said, “Data is the new oil. It’s valuable, but if unrefined it cannot really be used.” That refinement takes effort — and someone needs to own it before you can fully exploit its potential.

3. What happens if it gets something wrong — who’s responsible?

Generative AI tools are designed to produce confident, human-like responses. That doesn’t mean those responses will always be correct. And even when they’re factually accurate, they can still be inappropriate, unclear, or misleading in context.

Good implementation makes it easy for users to flag issues, check sources, and get a human view when needed. We have humble-bragged here before that our tools always give easy-to-verify citations, and are trained to do their jobs and provide advice rather than replace professional decision-making. More complicatedly, we also make sure we know who the client is and that they know how best to roll the solution out. We push back when they say, “Well, I guess it’s some combination of everyone on this call…” – change programmes need a sponsor.

If you are prepared to commission something, you have to be prepared to own it too, or find someone who will. How often have you become enraged by the HR or finance system you were told to use but somehow you can’t find a single person who admits to being the one that bought it and decided everyone had to use it? It’s odd, really, that we get mad at the system. It didn’t build itself, and it didn’t buy itself either.

I’ve made that sound cynical, but the solution is wholly uncynical and great craic – even if the thing you’re rolling out is very serious indeed. Make your AI purchase a transformation project. Ask, who will be the champion? Who will lead by example and sell the benefits? It beats someone being voluntold to just run the mandatory all-staff webinar. When it works, the confidence it brings to staff using it is transformative. Owning and leading change is fun.

4. Who maintains it — and what are we displacing?

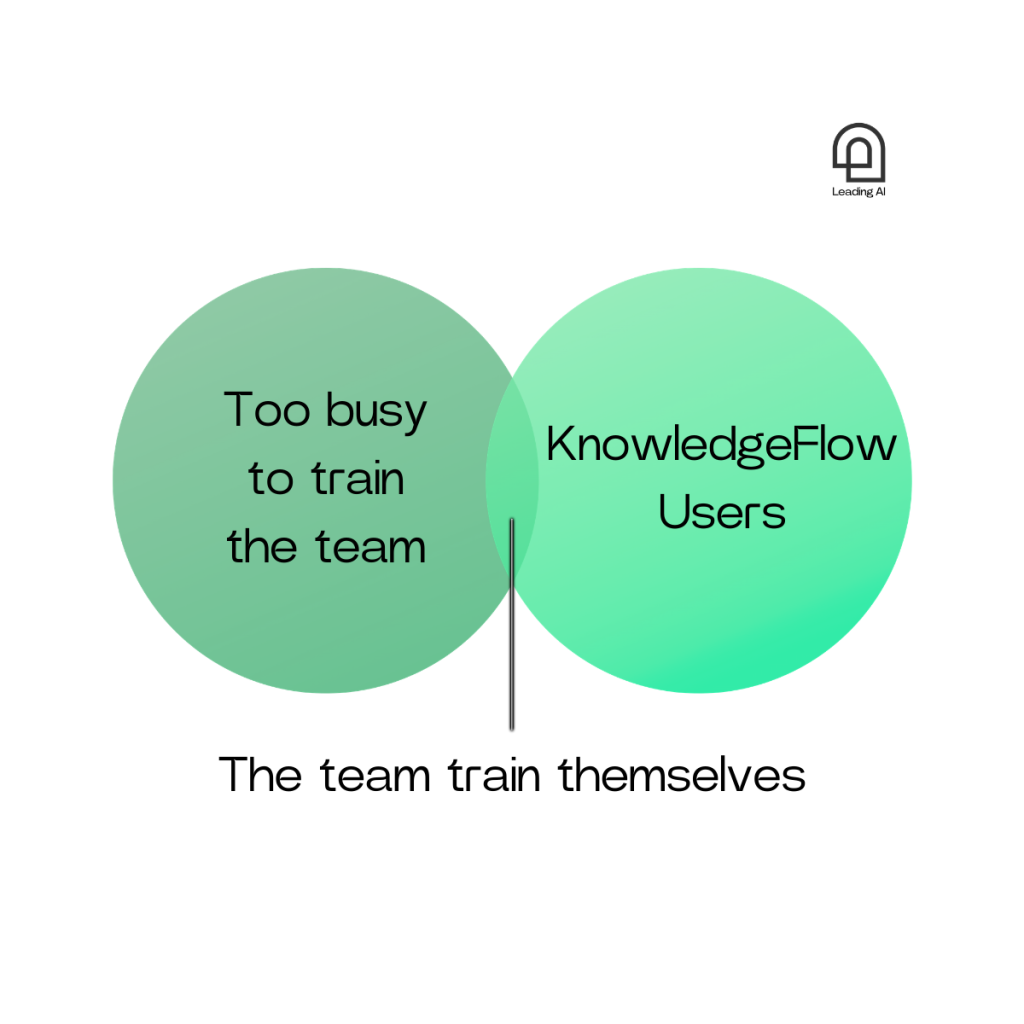

Sometimes your IT or digital team will be keen to build something themselves. That can be great — especially if the use case is tightly scoped and your team wants to learn by doing. It can be brilliant CPD. But enthusiasm isn’t the same as long-term ownership.

Ask:

• Who’s going to update it when the data or policies change?

• Who will support it when staff start relying on it?

• What other work is your team putting on hold to make this possible?

• Will it still work if the environment changes?

…and maybe just double-check if there is any evidence that this is the solution staff are asking to have built first, or just the one that made most sense to the developers. If you can, put in place some evaluation measures at the outset. Cost it realistically.

We’ve seen great results when teams partner early with suppliers who understand their world. One council cut days of admin each month by starting with a small, tested tool and giving frontline staff time to explore and shape it. The lesson wasn’t ‘move fast’—it was ‘move together.’

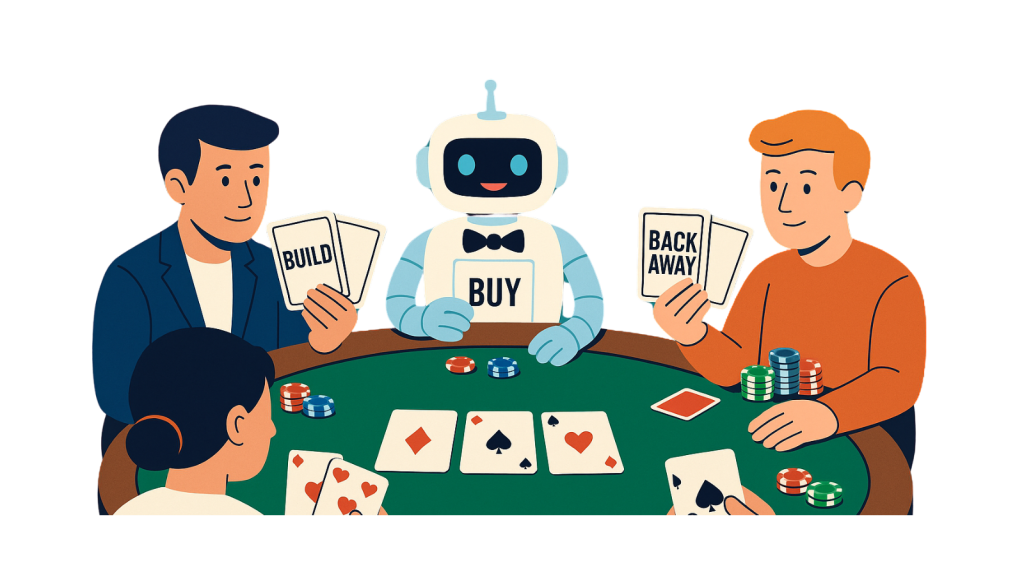

5. So, should we build, buy—or back away?

Does anyone else watch Love It or List It featuring Kirsty and her affable work husband, Phil? Kirsty works intensively with a family and their builders to try and make their current house work as well for them as it possibly can – usually by knocking through from the kitchen. Phil pops in once or twice and shows the family a few other properties they could buy instead. Then, after the work is done, the money is spent and everyone’s relationships have been tested to the kinds of limits you can only discover after six months of builder dust and having to make 20,000 joint decisions, the family has to decide whether to stay, or cash out. Love it, or list it.

It’s excellent fun, but I cannot watch it without someone in our house pointing out that the question is asked too late. The contestants… sorry, family… have already survived the worst part of staying put and renovating, and they look far too tired to pack up and move. The real question should be: if you could go back in time, would you bother with all that, or just move? You could have been in your new home six months sooner.

I realise that would be a different, and much shorter, show. I also realise that some people love the process and the uniqueness of the end result and, for them, it’s worth it. The point is: make it a conscious choice.

I might be stretching this comparison but: this is where procurement and leadership come together. If the problem you’re solving is not unique to you, there’s a good chance someone else has already built a good solution. Buying in doesn’t always mean big-ticket spending. It can mean working with a trusted partner or adapting something already tried and tested.

DIY is great when:

• The use case is truly niche and genuinely requires custom development.

• You have the people, budget and support to make it more than a side quest.

• You want to learn by doing — you’re clear-eyed about the limitations, realistic about the true cost, and you know what happens when it becomes a business-as-usual bit of kit to maintain.

Buy or partner when:

• You want something reliable, maintainable and already tested elsewhere.

• The risks of inaccuracy or poor implementation are high and an expert partner can help you stay ahead of those problems and add value in other ways.

• You’d rather focus energy on adoption and impact than infrastructure.

Sometimes the best choice is to hold off entirely, until your organisation is better placed to support or absorb change and you’re more confident about what you need and why you need it. However change-ready you feel, you can still work out:

a. what represents good value to you – what are you buying from your supplier relative to the benefits to you and the true costs of an alternative

b. at what stages you can pivot or hand over – know what scope you have to change tack. Be okay with cutting your losses.

FOMO, funding, and knowing when to fold ‘em

I don’t want to tell you that investing in innovation is a bit like gambling, because it’s nothing like making a bet on the Grand National. But it’s a bit like playing poker: skill has the edge over luck, but luck is a factor because you can’t know everything about what you’ll get in the draw. Spend what you can afford; take calculated risks.

We are easily caught between a desire to move fast and a fear of missing out, but whether you choose to build, buy, or back away for now, what matters is that your decision is grounded in the reality of what your organisation can support and sustain.

And if you’ve got a partner you trust—one who understands your world, isn’t afraid to challenge your thinking, and doesn’t flinch when things get messy—you might just get the best of all worlds: something that works, a team that learns, and a project you’re not afraid to show off to your board. Because you made it happen together.

*Clive Humby is a mathematician, data science pioneer, and the brains behind the Tesco Clubcard, which revolutionised data-driven retail and spawned a million more loyalty cards.