I rarely buy a lottery ticket, but when I do – and despite knowing the odds are stacked against me – I experience a brief, irrational moment of thinking: “Well, I’ve done the admin, so I’ll probably get something.” That’s just human nature. Most people have a little voice telling us that our past actions create a sort of obligation for a payoff. We instinctively understand cause and effect, and we don’t have time to consciously run the numbers behind every little choice we make.

There’s an anecdote my dad (a noted statistician) used to tell. He was on a tour of a casino with other senior statisticians. The casino owners laid everything pretty bare: the odds, the payouts, the long-term house edge. The statisticians understood it all and appreciated the transparency. Except one of them — highly experienced and professionally qualified — still argued: “I understand all that, but… if it’s been black five times in a row, red must be more likely next time, really.” The others couldn’t quite believe they were having to explain basic probability to their colleague and how each spin resets the odds. What happened on the last roll does not change the next. It feels like you’re due a red, but it’s no more likely to come up now than it was the first five times.

It’s these moments that create a mirror for what I sometimes see happening when organisations invest – especially when they invest in tech.

Understanding the Sunk Cost Fallacy

For the uninitiated, the sunk cost fallacy is our tendency to continue investing in a project (time, money, effort, reputation) simply because we’ve already invested so much — even when the rational decision is to stop, freeing us up to move on.

Past costs are irrecoverable; rational choice should focus only on future costs and benefits. But emotionally, that’s incredibly hard to do.

No one wants to shoot the horse. We’re fighting against our instincts when we do it, and we struggle to do the much harder sums involved in working out the opportunity cost when we press on despite seeing the measurable but indirect negative impacts and human toll it takes. Knowing it might ultimately cost more down the line feels too much like a ‘future you’ problem. Present-day you finds it easier to say yes than no.

Why the instinct is totally human

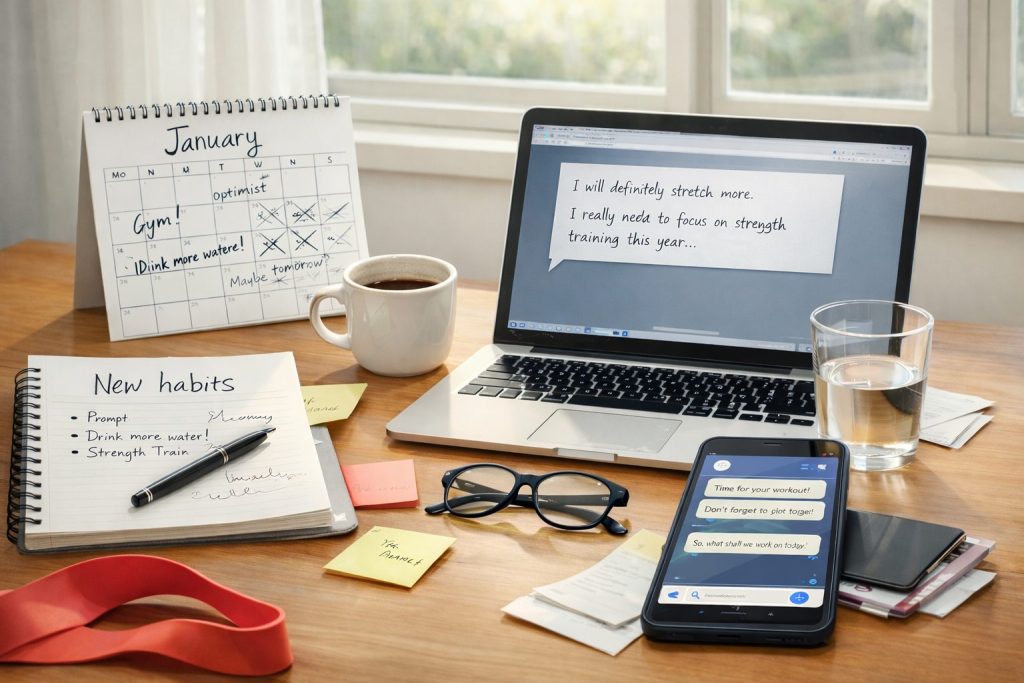

You’ve bought the licences, you’ve onboarded teams, you’ve committed budget and all that change management board time and you feel you should see something. It’s natural to think: “We’ve done the hard work — now the payoff must come.” But my lottery ticket moment of madness applies: you’ve played it properly, so you have to hope that playing alone justifies some sort of outcome.

When organisations purchase enterprise AI tools — say a full suite of Microsoft Copilot licences, or when you set out for a big AI platform on the promise it will resolve all the interoperability issues they’ve lived with for years — the human instinct is: “We’ve paved the road; it must lead somewhere.”

That instinct is not irrational. It’s part of our desire to justify effort, to validate investment, and to feel we haven’t wasted anyone’s time and money. But it becomes irrational when it dictates continuing rather than evaluating.

How it plays out in AI and other tech investments

Let’s say an organisation licenses Copilot (similar products are available…) across 10,000 users. After six months, usage is patchy, productivity is largely unchanged, the eye-rolling and illicit use of ChatGPT on phones are standard, but the board stands by their choice. Rather than revisiting the business case, they renew.

Legacy systems persist because “we’ve spent £X million already.” The consequence: mounting technical debt, slower innovation, frustrated teams, and missed opportunities.

Verified examples worth learning from

In leadership seminars, Concorde and the Channel Tunnel are often cited as examples of the sunk cost fallacy in action. I get it, but I’m too fond of both to play along with that, and I think different rules can apply to R&D and to public sector projects where a quick ROI isn’t really the point. We have to keep some train lines open when they’re not profitable. Ditto post offices. Also: there’s the romance of it all.*

But research on IT projects shows the risk is real: in a sample of 1,471 IT projects, while average cost overrun was 27%, one in six ended up with cost overruns of around 200%.

In app modernisation and digital transformation, organisations hang onto legacy systems because they can’t bear to abandon prior investment — yet the true cost is opportunity cost. Everything you didn’t do while you were busy with project doom.

These examples show the cost is not just the money already spent — it’s the momentum lost, the innovation blocked, the future value forgone.

What it means for your AI strategy, in practice

As per, we have some practical advice for you.

- Recognise the instinct – The simplest advice is that you need to notice when your reasoning shifts from “let’s evaluate” to “we must keep going because we already invested so much.” Poker players talk about being ‘pot committed’ as if it’s logical to press on because, well, we’re in it now. But it’s just another way of saying that you’re expending more chips despite the odds being against you, because you’re running on the hope that it’ll recover the chips you already spent. Which it almost certainly won’t (‘almost’ being the sliver of illogical hope…)

- Reset your decision-making lens to future value – Ask: Given what we now know, is this investment still the best path forward, or is there a better one? Past investment should not distort that question. Assess your options and the true costs.

- Track the right metrics – Evaluate adoption, active users, value delivered, cost per value unit — not just licence counts or modules deployed. Outputs aren’t outcomes.

- Set some exit criteria or pivot points – At the outset of AI initiatives, define what success looks like and what failure thresholds will trigger review or abandonment. Agree an evaluation plan as part of the plan. The decision is a lot easier to make if you have a built-in stop/go review point. Gives you an emotional run-up to the possibility of ‘stop’.

- Celebrate course corrections – Stopping an under-performing project is not failure: it’s discipline. Better to redeploy resources to something that can deliver. I can tell you from experience that everyone will move on quicker than you think – and the relief will bring a little positivity bump to more teams than you imagined.

- Avoid “faith in luck” thinking – Just because you’ve spent time and effort does not mean the next roll of the dice (the next phase of deployment) is more likely to succeed. The odds reset. Always. That’s why when you roll the dice six times, you don’t get each number once.

In poker, the moment to fold isn’t shameful; it’s smart. In AI, writing off a purchase is not a loss of face; it’s disciplined leadership. Beware of the snake oil salesman who promised the One Thing would solve everything. If it’s been nine months and you’re not feeling it, weigh up something that works for you (#ad, as they say on Insta).

If you’ve bought the chips, the smart move is: run the odds. Then decide. You can even count the cards: the tech market isn’t a casino. Work out what’s coming down the line. Spend what you can afford (and if that’s a Concorde just for the romance, that’s cool).

*Proof, if needed, these posts are still written by a human. I like Concorde because I do. I used to hear them fly by when I was a kid and climbed around one in a museum as an adult. I could probably write you a very rational sounding argument for investing in it, but the reality is: no modern passenger plane is as fabulous. And fabulousness costs.

Latest posts

AI is mainstream; the promised productivity gains aren’t. Why the gap persists.

News