Russia’s new humanoid robot, AIDOL, made its grand public debut recently and became an instant viral sensation for all the wrong reasons. It walks onto the stage to the Rocky theme, waves to the crowd and almost immediately faceplants. Then, incredibly, things get worse: handlers rush in, try to drag it behind a curtain, get tangled in the fabric, flail, and for thirty glorious seconds it looks like the local am-dram troupe having a go at budget sci-fi.

I’m not exaggerating. You’d struggle to write a skit this cringe: in any writers’ room, someone would say “too Benny Hill” and move on. If you haven’t seen it, it’s here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=s8hABHmA_NE. You’re welcome.

I watched it with an instinctive mix of embarrassment and, “Well, what did you think was going to happen when you picked that walk-on music?” Sometimes karma is very swift indeed.

I also realised something: I almost never write about AI and robots these days. Poor AIDOL made me think perhaps we should check in on those guys. See how the conveyor belt of prototypes is doing. Make sure they’re not weeping in a corner while the cooler LLM kids snigger and write wry one-liners about them.

So let’s do this. Let’s talk about why robots make me uncomfortable, why humanoid ones make everyone uncomfortable, and why the robots that actually matter are the ones nobody makes viral videos about — because, as with most Really Useful AI, it’s the boring ones that work best.

My issue with robots

There are two things.

First: robots are not really my thing, and I know my limits. My professional life is mostly about AI governance, responsible use, organisational readiness, and helping people get value out of reliable, bespoke generative tools in sensible, human-focused ways. That’s our thing at Leading AI. My day does not involve understanding hip actuators, and that’s how I like it.

Second: humanoid robots sit firmly in the uncanny valley for me. Not in a “they’ll overthrow humanity” way — although many people still fear that, a fear helpfully diminished by the AIDOL clip. My issue is more in a “why is that thing looking at me like it wants to make friends?” way. I get the same ick I get when someone has strong “pick me!” energy but it’s not at all obvious why they’d add value to my life.

Robots that look almost human but not quite spark something primal: fascination mingled with discomfort. I can write dispassionately about data governance and hallucinations, but put me in front of a robot with a silicone smile and my brain quietly closes the door and backs away.

AIDOL’s dramatic entrance (and exit) reminded me of something we talked about early on at Leading AI: that AI is neither good nor evil; it’s simply powerful and occasionally chaotic, and it has an image problem. Robots, more than any other part of AI, make the chaos very visible.

What the uncanny valley actually is

The “uncanny valley” sounds like something from a dystopian novel, but it’s a straightforward idea. When something looks nothing like a human, we’re fine. When it looks exactly like a human (or close enough that we can’t tell), we’re also fine. Hit the line in between — the valley — and things go a bit… weird.

A movement is slightly off and it’s like watching a human grafted onto a spider. A face is expressive but not quite natural and suddenly feels very wrong. A voice sounds human until it doesn’t nail the tone, leaving you wondering why it’s so reassuringly upbeat.

Our brains have evolved to read human faces and movement with ridiculous precision, so they notice the mismatch before we’re consciously aware of it. That’s why humanoid robots feel unsettling: they’re close enough to trigger our social instincts, but far enough away to violate them.

AIDOL didn’t just fall; it faceplanted into this psychological gap.

Strategy A: be adorable

To counter this, robot and AI designers have increasingly tried to sidestep the valley by going cute: big eyes, rounded edges, gentle movements, kawaii-style cartoon graphics, chirpy childminder voices. It’s how several restaurants have successfully rolled out robot waiters; my kids were very pleased indeed when one brought them fajitas.

Cuteness works because it signals harmlessness. It says, “Please don’t expect too much from me; I’m doing my best.” But it’s a knife-edge. Make a robot too cute and it becomes unsettling in a different way — like something that knows it’s performing innocence. Make it cute and humanoid and suddenly it’s both needy and uncanny. Give it a smile it can’t change and it looks delighted by everything, including its own malfunctions.

Weird cute sits right next to creepy cute. This kitten remains a strong example of the genre: https://www.leadingai.co.uk/blog/doesnt-everyone-have-a-favourite-ai-use-case/.

Strategy B: be boring

Humanoid robots dominate headlines because it’s easy clickbait, but — and I’ve checked — they’re not where most of the meaningful progress is happening.

The robots that are reshaping industries don’t have faces. They don’t pretend to be people. They don’t try to delight you. They just make themselves useful.

They are robotic picking and packing systems in warehouses; inspection robots like Boston Dynamics’ Spot operating in mines, factories and utilities (https://bostondynamics.com/products/spot/); and logistics robots that carry boxes, move pallets, scan inventory. There are also some impressive semi-humanoid industrial robots used simply because they can navigate spaces built for humans — not because they’re aspiring work besties (https://www.businessinsider.com/gxo-brings-humanoid-robots-to-warehouses-2025-4).

These are the fellas that don’t go viral, but they work. Consistently, quietly, and increasingly well.

And if we’re asking where AI-powered robotics will genuinely change lives and economies, it’s here — in the dull, efficient, necessary tasks humans either dislike or shouldn’t be doing. And that brings us safely back to what we know: AI transformation is rooted in neat, sometimes boring, useful, reliable tools, not in big, all-singing, awkwardly dancing, flashy tech.

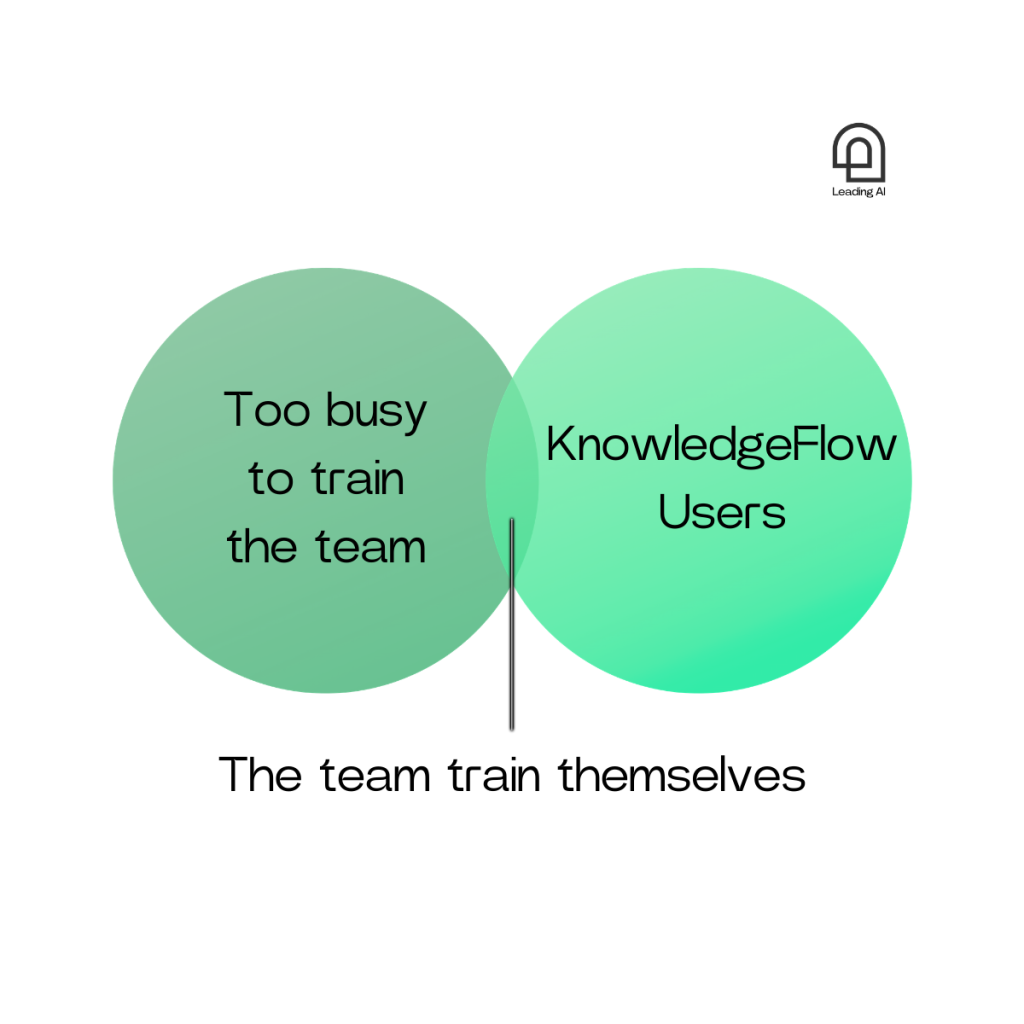

There’s a lesson in this for organisations: resist the shiny demo. Choose the dependable tool.

Where this leaves us in our wander along the uncanny road

For me, we land somewhere very human. Robots tell us more about ourselves — our expectations, anxieties, and hopes — than they tell us about technology. We project personality onto objects with joints. We forgive software for mistakes but recoil when something vaguely person-shaped misses the mark.

One of our earliest blogs – https://www.leadingai.co.uk/blog/opportunity-and-risk-why-ai-is-neither-a-good-nor-b-evil-but-still-c-both-neither/ – argued that AI isn’t good or evil; it’s a mirror. The uncanny valley is a mirror too; one that reflects our discomfort rather than our potential. And that’s helpful, because appearance and capability are not the same thing.

When organisations consider how to use AI, the takeaway is simple:

- Don’t chase whatever looks most futuristic.

- Don’t mistake charisma for competence.

- Choose what is useful, safe, reliable (even if it’s a bit boring).

- Choose what makes work easier, not what makes headlines.

Humanoids may eventually find their footing. In the meantime, the robots that matter are the ones doing dull, essential jobs safely and consistently — not the ones waving on cue and hoping not to trip over the curtains.

Some robots are elegant, some awkward, some quietly transformative… and some are best left backstage until someone sorts out the calibration and resists the grandiose walk-on music.