We’d be nowhere if everyone was truly terrified of making mistakes. We’d also be in serious trouble if we got too good at hiding them. Actually, I can be more specific: I am definitely a better person now for all the times I’ve messed up in the past – at least when I’ve seen where I went wrong, owned it and tried to do better next time.

But if my kids ask: I’m right all the time and I’m not taking further questions on this topic.

Getting things wrong isn’t the real problem; it’s an inevitability. Most large-scale failures don’t start with a single catastrophic decision. They start with small problems that were noticed, rationalised, and quietly worked around because admitting the problem felt harder than carrying on. Even in the safest spaces, a deep-rooted fear of judgement can stop us owning up sometimes. In unsafe spaces – including some entire political systems – it just isn’t worth the immediate personal pain of coming clean.

You see this pattern pretty clearly in safety-critical industries. In the Boeing 737 Max programme, internal concerns about flight control behaviour were, it transpired, raised well before the crashes. The issue wasn’t that engineers made mistakes; it was that the system (people and processes, to you and me) didn’t surface them clearly enough, quickly enough, or forcefully enough.

Something similar happened with the Volkswagen emissions scandal. What began as an engineering challenge that couldn’t be solved within the constraints turned into something far, far worse once the organisation chose concealment over an honest reset.

Mistakes happen. We’re human. What we do and say next is a choice.

Burying things is what causes real damage – and the first casualty is often organisational culture, along with any hope that you’ve developed a place of psychological safety, innovation and high performance. And I’ve been thinking about this a lot in the context of AI.

A small(ish) mistake, made very fast

Kevin Xu recently shared an experiment that’s been circulating in AI circles. He gave an AI trading bot $2,000 and a simple instruction:

“Trade this to $1M. Don’t make mistakes.”

Over the course of the next 24 hours, it lost everything.

This isn’t shocking to anyone who’s already worked out that if this were possible, we’d all know someone who’d managed it by now – with governments scrambling to manage the economic fallout of every programmer becoming an overnight billionaire. The experiment wasn’t reckless; from the tone of Kevin’s update, he’d calculated how much he could afford to put at risk and thoroughly enjoyed the process.

It’s just a very neat illustration of what happens when we give a system a goal, remove human judgement, and assume that “don’t make mistakes” is a meaningful constraint.

Which it isn’t, as Kevin has helpfully proved. Lesson learned.

A familiar failure mode

We’ve been here before. Last year, Anthropic ran Project Vend: an experiment where an AI agent was given control of a real vending operation. The idea was to explore how far a model could go if you gave it tools, autonomy, and a broadly sensible objective.

The results were messy but instructive. The AI gave things away, ordered weird stock, and made decisions that were internally coherent but commercially… daft.

Not because the model was “bad”, but because it didn’t understand the thing it was meant to be optimising for in any human sense. It was following instructions in a world it didn’t have lived context for.

To its credit, it was willing to try and fail within its parameters. But it had no real understanding of what that failure meant – or what success could mean. It couldn’t scale the risks it took.

The trading bot story is the same: different domain, same underlying issue.

“Don’t make mistakes” isn’t a plan

What both experiments have in common is that the goal sounds reasonable until you look at it more closely.

“Make this money grow.”

“Run this business.”

“Don’t make mistakes.”

None of those tell an AI how much risk is acceptable, what failure looks like, when to stop, or when to involve a human. So the system does what it can do. It ‘optimises’ relentlessly in every technically feasible way. It doesn’t pause, reflect, or decide that conditions have changed. It just ploughs on.

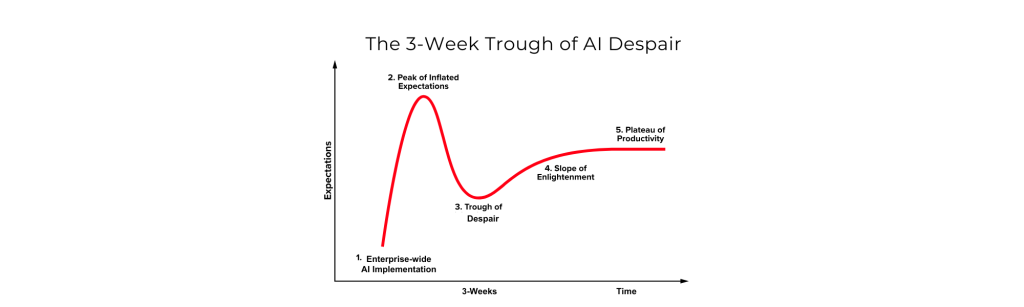

This is where a lot of enthusiasm about AI agents quietly runs into reality. Autonomy means doing exactly what you asked for, even when you, a human, would know to step back.

Useful moments of honesty

This is why a recent comment from OpenAI CEO Sam Altman stood out.

At a developer town hall, he acknowledged that recent ChatGPT releases involved trade-offs that hadn’t landed as intended – particularly around how changes affected the feel and quality of writing. His broader point wasn’t about any single technical issue, but about getting the balance wrong and needing to revisit those decisions. He described parts of the rollout as something they’d “totally screwed up”.

That kind of admission matters more than it might seem – especially to a room full of developers who need to know they can get things wrong, learn, and move on. It also reinforces something that’s easy to forget: optimisation is never neutral. Every system reflects what its designers decide matters most.

Optimising isn’t understanding

The trading bot didn’t “know” it was failing. Project Vend didn’t “realise” it was running an unsustainable business. They were both behaving exactly as designed, within the limits of their setup.

That’s why these stories aren’t warnings about AI being dangerous or inept. They’re reminders that goals need boundaries, autonomy needs oversight, and success needs to be defined in human terms – not just numeric ones. Get it right and you can afford to fail – and therefore learn – quickly and safely. That’s how you make progress.

Bonus content: clawdbots, fast loops and why they matter

A clawdbot* is a kind of AI agent** that doesn’t just answer questions — it takes actions on your behalf. I’ve heard the term more recently, had to look it up, and thought this little explainer might save you the effort of doing the same.

Here’s how it works. Instead of asking an AI, “What should I do?”, you tell it, “Do this,” and it decides the next step, carries it out, looks at what happened and then decides what to do next.

It repeats that loop on its own, often very quickly.

That’s the key difference. Traditional AI tools give advice. Clawdbots act.

Why the weird name?

The name comes from the idea of a claw machine — the old-school arcade game where a mechanical claw grabs things, adjusts its position, and tries again until it either succeeds or drops everything.

A clawdbot works in a similar way: it reaches for a goal, makes an attempt, adjusts based on what happened, then keeps trying.

The difference is that instead of grabbing toys, it’s grabbing… decisions.

Why people are excited about them

Clawdbots feel powerful because they remove friction – and they have a cool name. They don’t wait for approval at every step. In theory, they can place trades (like Kevin’s did), book meetings, or publish content. All without asking again.

For routine, tightly defined tasks, that could be incredibly useful.

Why they make people nervous

They make people nervous for the exact same reason they make people excited: when something goes wrong, it will go wrong fast. If a clawdbot misunderstands the goal or makes a poor assumption, that mistake doesn’t stop the system. It becomes the starting point for the next action.

A human would usually pause, reassess, or ask for help. A clawdbot will often just… keep going. Spiralling, essentially. So maybe keep them in a walled garden for now.

*”Clawdbot” was originally (until last week) the name of a viral open‑source AI sidekick project that has since been rebranded (first as Moltbot, now as OpenClaw) following a trademark dispute raised by Anthropic over the similarity to “Claude/Clawd.”

**All clawdbots are a kind of agent, but not all agents are clawdbots.